Quick Tanks: The Best of Long-Form Defense Analysis, Briefly

A weekly review of the long-form content from the national security policy, defense policy, and related technology analysis community.

Good afternoon, defense buffs.

This week, I have three intriguing reports to share with you all. Their topics include:

The current shortfalls of UK Defence training and the various ways to modernize it

How US Central Command (CENTCOM) can mitigate climate-related conflicts in its area of responsibility

The geographical distribution of China’s AI job market and its defense-related trends

Quick Tanks is a weekly collection and summary of the latest long-form analytic content on the topics of US defense, force structure, innovation, and policy considerations. We strive to aggregate all of the key sources of analysis and present brief, neutral summaries to help keep you informed. Should you feel inclined to learn more about any study, please reference the full report via the links provided.

The sponsor of the newsletter is the Hudson Institute’s Center for Defense Concepts + Technology.

Tank you for sharing and subscribing, and happy reading.

‘Goodbye Mr Chips?’

Modernising Defence Training for the 21st Century

By Paul O’Neill and Major Patrick Hinton

Royal United Services Institute

Link to PDF; Link to Report Page

Focus: The report provides an in-depth review of UK defense training for service members, examining the overarching framework, key challenges, and potential areas of modernization.Analysis: The report employs a qualitative analysis drawing on 32 structured interviews with defense and training experts, training doctrine, and literature reviews.Argument: The current training system, while substantial, is rigid and struggling to meet the rapidly changing skill demands of 21st-century warfare. Specifically, challenges to modernizing defense training remain in the culture, system governance, process, training delivery, learning environment, and workforce.Insights: Positive initiatives and practices in defense training exist, but they remain narrowly scoped and require expanded sharing of lessons learned across the services. Secondly, external commercial expertise, if properly leveraged through partnership, can complement the strengths that defense instructors offer. Thirdly, improvements in data quality and availability are lacking, but they are essential to guide modernization efforts.Recommendations: UK Defence should 1) implement comprehensive upskilling initiatives for all defense training staff, not just frontline instructors, 2) promote flexible, tailored learning journeys for individuals, 3) enhance training data use and strengthen connections between training components and wider human capital management flows, and 4) pursue deeper symbiotic partnerships with commercial training providers to access external expertise.This RUSI report provides an insightful examination of how the UK’s military training systems need fundamental modernization to prepare the armed forces for intensifying 21st-century threats. The report conducts an incisive audit of systemic training challenges across the domains of culture, governance, process, delivery, environment, and workforce. It then delineates pragmatic opportunities to evolve training through enhancing expertise, adopting progressive delivery methods, improving system oversight, and partnering with industry.

First off, the report identifies cultural problems with UK defense training, including a mechanistic, industrial approach focused on standardized training rather than individual learning journeys. There is also a narrow conception of "talent" in defense, seen as those rising to senior ranks rather than a wider group making significant contributions. Relatedly, training is designed as a badge of honor to pass, rather than to help people succeed. Moreover, there is insufficient recognition of prior learning gained outside formal defense programs, unnecessarily extending the training process for some individuals.

On system governance, the absence of an integrated view of defense training as a whole causes fragmentation, a lack of clear accountability, and a disconnect between training output and strategic capability needs. Specifically, individual and collective training elements are separated rather than bridged, training requirements are disconnected from delivery limitations, and new mandatory modules are added without assessing costs or trade-offs. Additionally, when trying to increase efficiency, officials tend to transfer risk rather than mitigate it, with training responsibilities passed to the frontline without appropriate resources. Lastly, multi-year cycles to update core training content are too infrequent given the pace of change in 21st-century conflicts.

Furthermore, the report finds that the formal Defence Systems Approach to Training (DSAT) process struggles in practice despite having worthy conceptual elements. For one, DSAT processes are under-resourced and not well understood by key staff — the publication outlining the DSAT process is 617 pages. Secondly, the process is overly complex and bureaucratic, lacking responsiveness to keep pace with changing training needs. Similarly, managing training pipelines and contracts with external providers follows rigid specifications rather than flexible partnerships. Consequently, this restricts the adoption of innovative instructional approaches and technology that could enhance outcomes.

“It is not just instructors who lack deep knowledge and skills. TRAs and training support staff such as course designers and those developing training materials receive little training. Analysing and determining how best to close training gaps, and knowing what learning technology is available and how it can be best employed are not easy, but these skills are often assumed to be acquired through osmosis or with limited formal interventions (for example, the Defence Online Learning Course, for those responsible for developing online learning, lasts two days). Moreover, the lack of training for those people managing training means that they are often unfamiliar with the DSAT process and can default to slavish adherence to the letter of the process rather than deviating from the formal rules to achieve its intended purpose where necessary.”

To overcome these obstacles, the analysis delineates pragmatic opportunities including:

“Upskilling the Defence training workforce – not just instructors, but staf across the training system, including TRAs, training managers and designers, and those validating the learning.”

“Adopting a less mechanistic, more organic approach to delivery – one that facilitates unique individual journeys through the training system, gives more power to learners, and provides the right learning environment, enabled by modern learning technology.”

“Building a stronger understanding of the systems within which training sits, including the individual/collective training continuum, and better use of training data and its connection with recruitment and career management, which is how Defence applies the skills people have learned. The shit also needs to normalise the (impressive) response to the Covid-19 pandemic that oten stands out as an exception to the standard approach.”

“Building stronger partnerships with providers who can complement the strengths Defence instructors bring to the training system (their up-to-date operational knowledge and ability to contextualise the learning) through a stronger understanding of andragogy and best practice outside Defence.”

In summary, this incisive report lays bare systemic training inefficiencies and proposes insightful ways forward to cultivate appropriately skilled, responsive forces prepared for multifaceted 21st-century contingencies. I urge interested readers to look into the full report.

Defense Planning Implications of Climate Change for U.S. Central Command

by Karen M. Sudkamp, Elisa Yoshiara, Jeffrey Martini, Mohammad Ahmadi, Matthew Kubasak, Alexander Noyes, Alexandra Stark, Zohan Hasan Tariq, Ryan Haberman, and Erik E. Mueller

RAND Corporation

Link to PDF; Link to Report Page

Focus: The report examines how the US Central Command (CENTCOM) can use operations, activities, and investments (OAIs) to prevent or mitigate climate-related conflict.Analysis: The report analyzes historic patterns of US military interventions globally and estimates rough costs of intervention types. It also identifies causal pathways from climate hazards to conflict and possible interrupting factors. Data sources include a RAND military intervention dataset and USAID situation reports.Argument: The report argues climate hazards will exacerbate conditions and be a threat multiplier for conflict in the CENTCOM region. As a result, CENTCOM has a role in interrupting climate-conflict pathways and preparing to respond to resulting crises.Insights: Climate change will likely shift CENTCOM's focus from warfighting to responding to both traditional and nontraditional security threats. For instance, CENTCOM can play a supporting role to other agencies in preventing climate-related conflict through niche military operations and activities, which can interrupt pathways from climate hazards to conflict. Moreover, if climate stresses lead to more conflict, stabilization operations would likely impose the highest costs on CENTCOM given historical US interventions, whereas other operations like disaster response and counterterrorism have had lower costs.Recommendations: CENTCOM planning staff should incorporate climate projections and intelligence into theater campaign plans and operations plans. Moreover, CENTCOM should request the expansion of the National Guard State Partnership Program within the region, focusing partnerships on climate and disaster response experience. In addition, CENTCOM would benefit from greater climate literacy education among headquarters staff and forward-deployed personnel. As climate change threatens to intensify instability within the US Central Command area of responsibility (AOR) over the coming decades, this RAND report delves into how CENTCOM can leverage OAIs to interrupt causal pathways from climate hazards to conflict. Indeed, not only are the countries in the CENTCOM AOR historically prone to intrastate conflict, but they’re particularly vulnerable to climate impacts such as extreme heat and water scarcity. With the increasing likelihood of climate-related conflict endangering regional security, the authors argue CENTCOM must adapt to support both traditional and nontraditional missions.

Specifically, the report outlines several OAIs that offer potential “off-ramps” along climate-conflict progression. Empowering partners through innovative programs like the National Guard’s State Partnership Program could significantly bolster disaster response capacities. Secondly, strategic investments in logistical resilience provide dual military and humanitarian benefits. Moreover, information operations exposing violent groups’ cynical climate exploitation could undermine their appeal. Improving security governance and border control are further stabilization tools during climate-related contingencies.

Outside of security concerns, climate adaptation cooperation also provides opportunities — CENTCOM can leverage regional expertise while cementing bonds between coalition partners. For instance, Israel’s incorporation into CENTCOM enables it to contribute extensive experience with climate-adaption technologies, particularly in desalination. Combined with the UAE’s efforts around sustainable energy transitions and investments, these partnerships can accelerate adaptation and resilience. Collaboration on cleaner fuels adoption and shared climate-resilient infrastructure and products provide opportunities to strengthen the readiness of US regional allies against shared threats. However, given the complex web of relationships and competitors in the region, any technology transfers or shared products require judicious safeguards to prevent unauthorized proliferation.

“CENTCOM is not the primary U.S. government agency with the mandate and capabilities to break the progression from climate hazards to conflict, but CENTCOM does have an important supporting role to play via military-led OAIs. Specifically, CENTCOM could help interrupt the progression from climate hazards to intrastate conflict by developing partner forces with improved security governance, enhanced disaster response capabilities, and more resilient logistics, among other activities.”

Furthermore, the report analyzes four intervention types relevant to the CENTCOM AOR: stabilization operations, noncombatant evacuation operations, humanitarian assistance/disaster relief (HADR), and counterterrorism. Of these, stabilization operations have proven the most resource-intensive by an order of magnitude, with the total costs of individual NATO and UN-authorized missions ranging from $5.9 million to a striking $18.9 billion in analyzed cases from 1999-2012. This cost profile suggests CENTCOM should anticipate massive resource demands from stabilization efforts driven by climate-exacerbated state fragility, despite likely growth in lower-cost humanitarian and evacuation activities.

The report ultimately provides recommendations that could strengthen CENTCOM’s readiness across multiple areas. First, CENTCOM should hone its prioritization of nontraditional security cooperation to focus more narrowly on building climate resilience. Additionally, updating CENTCOM plans and intelligence with climate projections would allow for proactive responses as threats emerge. Forging partnerships centered on climate-vulnerable nations could serve to deepen vital disaster relief abilities where they are needed most. Finally, comprehensive education aimed at aligning staff proficiency with the growing impacts of climate factors would cultivate critical climate literacy at all personnel levels within CENTCOM.

To fully appreciate the report’s analysis and findings, I urge readers to examine the full report.

Assessing China’s AI Workforce

Regional, Military, and Surveillance Geographic Clusters

By Dahlia Peterson, Ngor Luong, and Jacob Feldgoise

Center for Security and Emerging Technologies

Link to PDF; Link to Report Page

This CSET report provides an in-depth examination of China's artificial intelligence (AI) job market through an analysis of over 6 million job postings. The authors filtered down the dataset to 58,229 technical AI job postings which they geographically mapped. Through their analysis, they identify major AI talent hubs across different regions and cities in China. Moreover, the report considers AI job postings in areas salient for national security — those advertised by defense-affiliated universities and military entities as well as postings related to surveillance techniques.

Their key findings are as follows:

78% of AI job postings are concentrated in three major economic/tech hubs: Yangtze River Delta, Pearl River Delta, and Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei area.

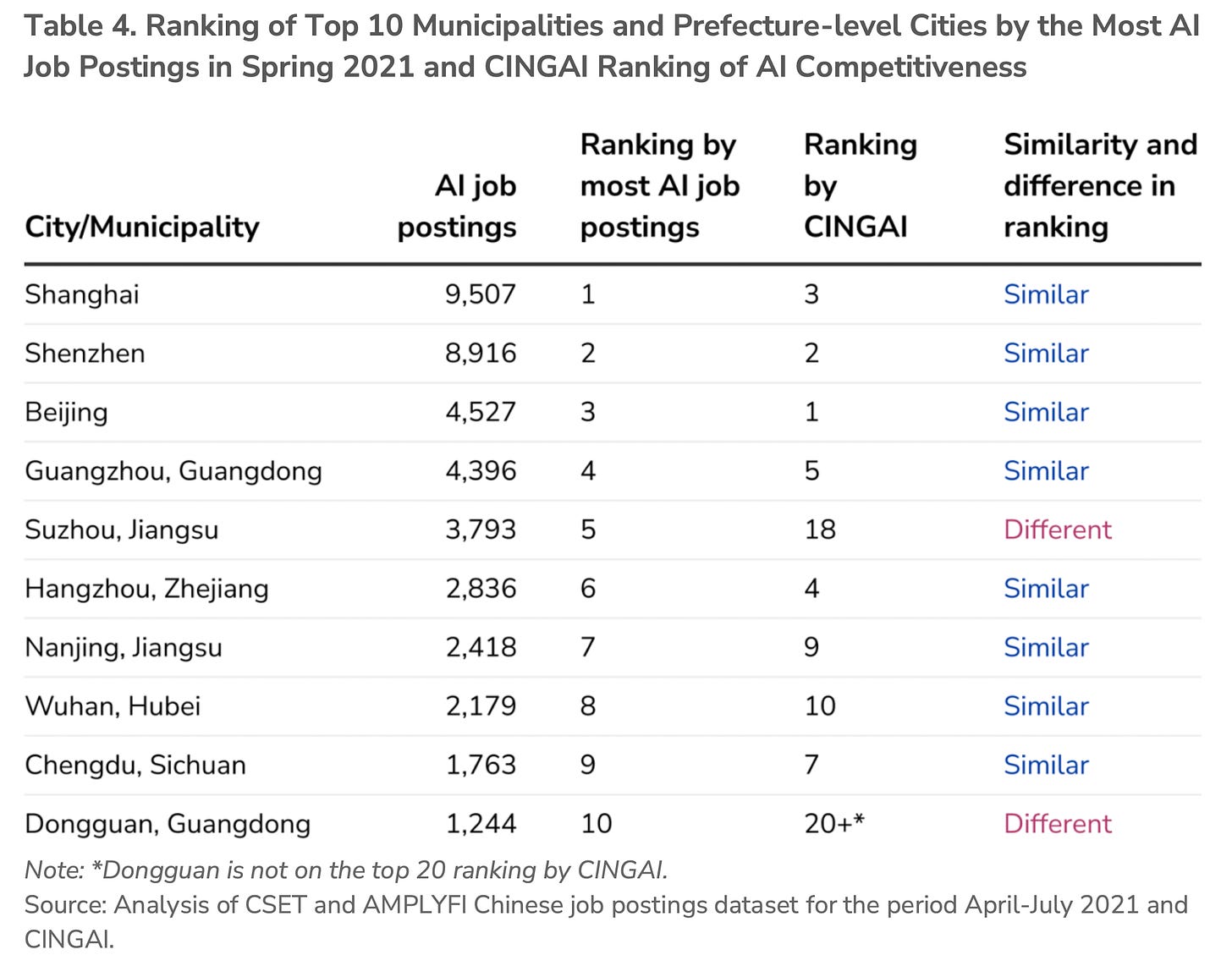

71% of AI job postings are in just 10 cities, with the top cities being Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Beijing.

“As Table 4 shows, the demand for AI talent, as proxied by our data on AI job postings, is concentrated in cities with vibrant innovation ecosystems which ranked high on CINGAI’s “AI competitiveness” index. However, there are two exceptions: Suzhou in Jiangsu province and Dongguan in Guangdong province, which are in the top 10 cities based on the number of AI job postings in our dataset, but fall outside of the top 10 regions in the CINGAI AI competitiveness ranking. The CINGAI report ranks Suzhou in 18th place, with a score of 8 out of 100, indicating a relatively underdeveloped AI innovation ecosystem based on the aforementioned factors considered in the index. Based on our data, however, Suzhou had the 6th-most AI job postings, with 3,793 job postings or 6.5 percent of the total AI job postings in our dataset. It is possible that Suzhou city's growing robotics industry may be driving some of this demand for AI talent. For instance, 51 percent of the AI job postings in Suzhou include the keyword “robotics,” compared to 34 percent of all AI job postings in our dataset. The CINGAI report also finds the AI ecosystem in Dongguan to be relatively underdeveloped. The city, however, makes our top 10 based on its demand for AI talent. While we cannot measure trends over time with our data, it is worth watching whether the AI-related job market in Dongguan is expanding, and whether additional investment and other resources are being channeled into the city to establish it as an emerging AI hub.”

79 AI job openings were advertised by 9 defense-affiliated universities across 10 provinces while the People’s Liberation Army posted just 2 AI-related jobs.

2,877 AI job postings related to surveillance were found, concentrated in Guangdong, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Beijing and Zhejiang. Of those postings, the most prominent keywords were facial recognition, feature extraction, speech recognition, sentiment analysis, and safe cities.

To learn more about the report’s methods and analysis, I urge readers to delve into the full report.